The Success Rate of Passive Funds

Morningstar’s Active/Passive Barometer does not provide a success rate for passive funds, but the exercise of estimating one provides additional insights into the Barometer’s methodology and the success rate of actively-managed funds.

In our recent research brief “Rethinking Survivorship Bias in Active/Passive Comparisons,” the Active Managers Council reviewed the methodology of the Morningstar’s Active/Passive Barometer, focusing on its approach to survivorship bias adjustments. We concluded that the Barometer’s methodology resulted in an overly negative assessment of active manager’s skill, and we proposed an alternate approach to calculating success rates using passive fund survivorship rates that we believed resulted in a more accurate estimation of that skill.

However, we also suggested that another approach could be insightful—namely, adjusting the performance of the passive funds in the category used as a benchmark. In this update to our brief, we explain how calculating a success rate for passive funds – and comparing it to the success rate of active funds – provides another means of evaluating active managers’ skill.

Estimating a Success Rate for Passive Funds

Using published data, we can easily establish the maximum value of the success rate for passive funds. It is equal to the survivorship rate for passive funds, which is a data point that Morningstar provides. (Recall that in Morningstar’s methodology, only those funds that survive have the potential to be “successful;” conversely, funds that are merged away or closed prior to the end of the period are, by definition, “not successful.”)

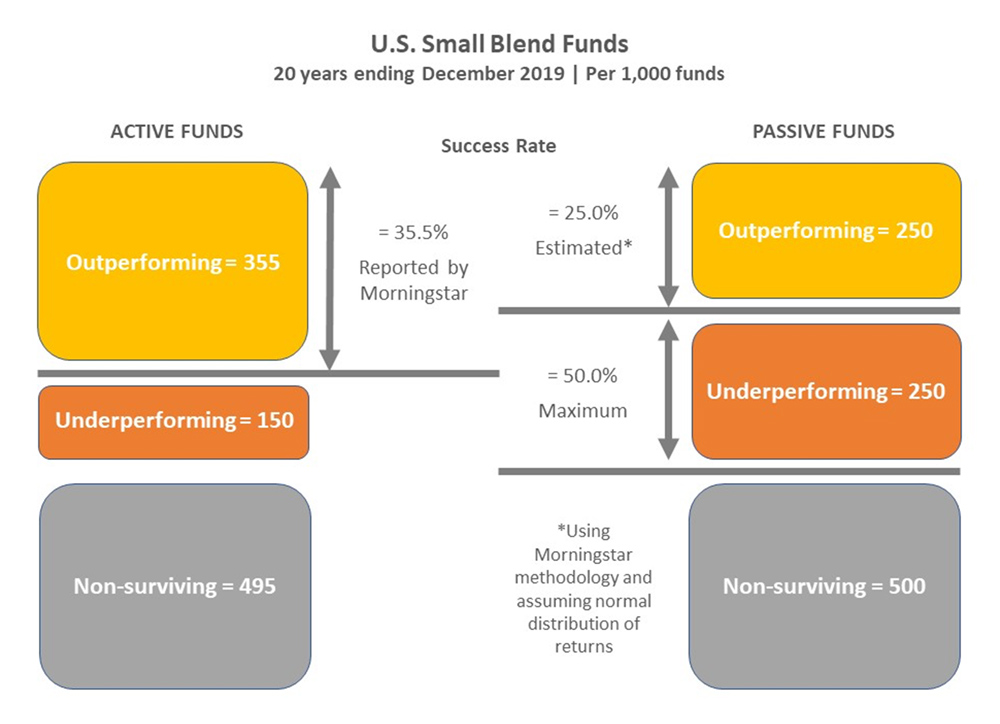

Continuing our focus on the U.S. Small Blend category, we observe that, for the 20-year period ending June 30, 2019, the passive fund survivorship rate is 50.0%. Therefore, the maximum success rate for these funds is 50.0%.

To make a more precise estimate of the success rate, however, we must make assumptions about the distribution of the returns of the passive funds. To be successful in the Active/Passive Barometer, a fund’s return must exceed the average return of the passive funds in that category. (This is the standard applied to actively-managed funds as well.)

Let’s begin by assuming that the returns of the surviving passive funds are normally distributed, which means that the average return in the category equals the median return. Put more simply, we assume that half of the surviving funds do better than average (and are successful), and half do worse.

In our U.S. Small Blend example, the assumption of a normal distribution of returns leads to an estimate of a 25.0% success rate over the 20-year period, which equals half of the survivorship rate for this group of funds. In other words, for every 1,000 funds at the beginning of the period, 500 were merged away or closed by the end of the period; of the 500 surviving funds, 250 outperformed the average fund and were “successful,” and 250 underperform.

Under the assumption of a normal distribution, the estimated success rate for passive funds of 25.0% is significantly lower than the published success rate of 35.5% for the active funds in the category. The differential between the two provides an indication of the degree of skewness in the return distribution that would be required for the passive success rate to equal or exceed the active success rate.

Overall, the comparison suggests that active and passive funds are more similar than the headline statistics would suggest.

Background: Reasons for return dispersion

The dispersion of returns among surviving funds is driven by the following factors:

- Benchmark choice (active and passive funds). While all of the funds are included in the U.S. Small Blend category, they may track or be measured against different index benchmarks. Therefore, differences in benchmark performance will lead to performance variation within the category. This factor, which can have a significant impact on comparative returns, affects both active and passive funds.

- Fee differences (active and passive funds). In addition, funds in the category often charge different fees. The management fees may vary, and funds can have different fee structures: some funds may charge only a management fee in an unbundled structure, while other funds may bundle together a management fee, recordkeeping charges, and marketing fees. Again, fee differences play a role in return dispersion for both active and passive funds.

- Tracking error (passive funds). Even if index funds use the same benchmark, they may experience variation in tracking errors, as a result of different trading strategies, replication strategies, etc.

- Active decision making (active funds). The managers of actively-managed funds make different decisions about securities to buy and sell, which contributes to return dispersion. Active decision-making will generally have a larger impact than tracking error, though size of the differential will vary by asset class and time period.

To summarize, return dispersion for both active and passive funds is driven by benchmark choice and fee differentials. Passive funds are affected by tracking error, while returns for active funds are influenced by active decision making. Because the return variation due to active decision-making is generally larger than the return variation due to tracking error, the range of returns for active funds is likely to be larger than the range of returns for passive funds.